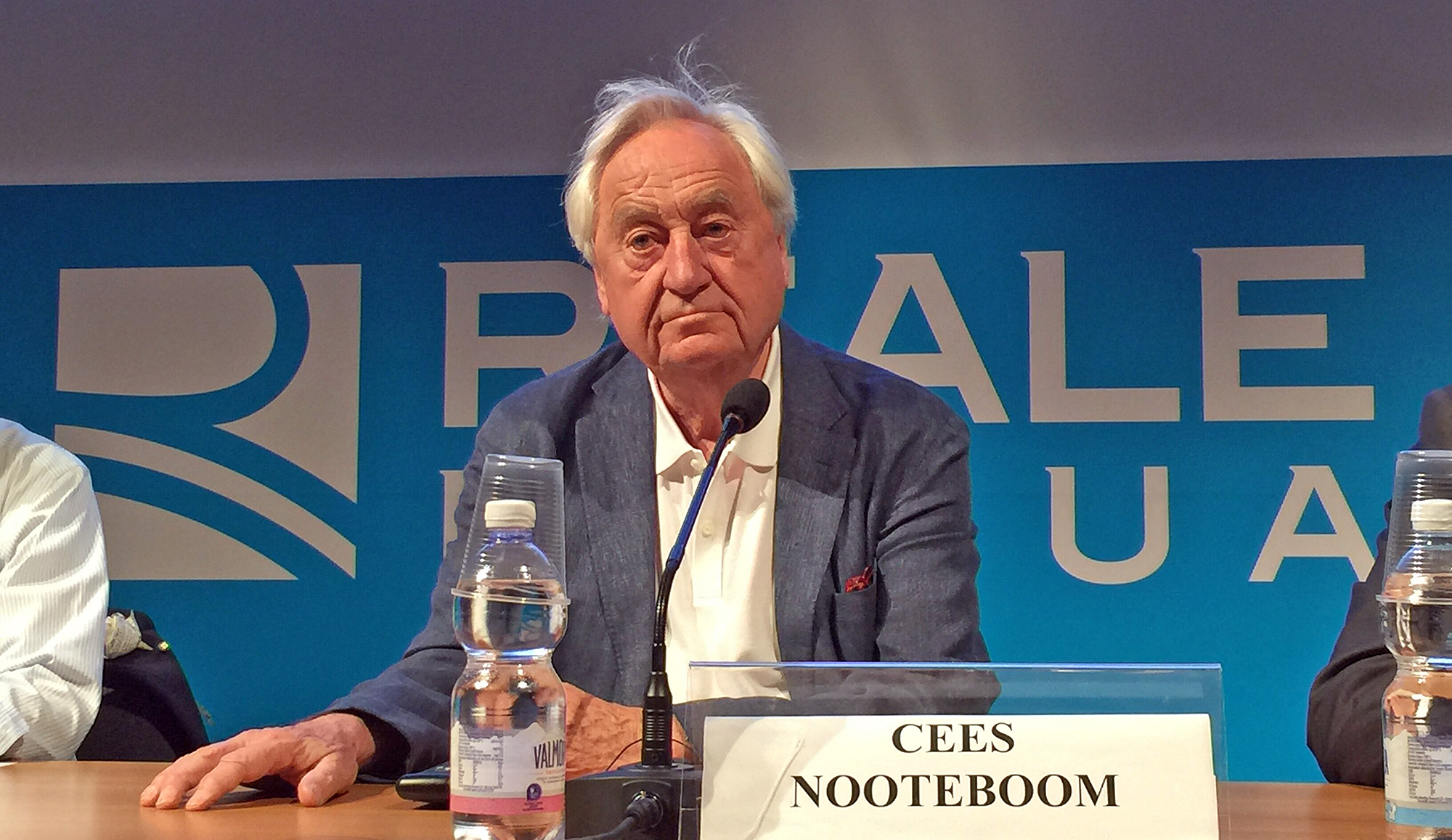

The Dutch novelist Cees Nooteboom died at the age of 92 in his adopted home of Menorca.

ISLAMIC TIMES – Cees Nooteboom died at the age of 92 in his adopted home of Menorca. With him, Europe loses a quiet, keen-eared chronicler of roads and journeys—a travel writer who took travel seriously as a way of being.

He was born in 1933 in The Hague and for decades has been regarded as one of the most important European authors of the postwar era. His work includes novels, short stories, poetry, essays, reportage, and above all travel books, translated into numerous languages.

For Nooteboom, travel was not a genre but a state of life. He lived and worked in many places across Europe—repeatedly in Berlin as well—and he did not seek the exotic as mere backdrop, but movement itself as a form of knowledge.

He approvingly quoted the insight that a person comes to know himself while traveling, and he understood being on the road as a school of perception and worldly understanding.

Photo: ActuaLitté/via Wikimedia Commons | Licence: CC BY-SA 2.0

In books such as Nooteboom’s Hotel, he distills the world into miniatures from hotel rooms: fleeting encounters, precise observations, and the quiet wonder of the traveling essayist.

533 Days: Reports from an Island carries this writing into duration: on Menorca, the journey becomes a rhythm of life; nature, reading, and Europe’s present intertwine into a quiet diary of attentiveness.

And in Venice: The Lion, the City and the Water, return and memory condense into a late portrait of a city—a meditation on beauty, transience, and the water that carries everything and changes everything.

His text “Farewell to Granada — The Blind Man and the Script,” from the volume Travels Through the Islamic World, is among the best things I have ever read. The description of his visit to the Alhambra in 1992 not only demonstrates the author’s linguistic mastery; it also allows the reader to take part in a metamorphosis.

After a stay in Tehran’s Winter Mosque, Nooteboom initially held the view that Arabic art was inhuman because it depicted neither faces nor figures he could hold on to.

Photo: Ninara/via Wikimedia Commons | Licence: CC BA-SA 3.0

Years later, during his visit to the Alhambra’s Court of the Lions, he recognizes another dimension of understanding: writing. What he first takes to be mere ornamentation on a fountain reveals itself, on closer inspection, as words.

He discovers “an arabesque current that runs after itself, that flows back into itself.” Not only does the world move; so, do the characters that describe it. Here, the writer concludes, space explains itself through what is written.

Nooteboom’s travel books are less reportage than reflective, attentively observed contemplations in which exact perception, historical awareness, and poetic condensation come together.

Many obituaries call Nooteboom “Europe’s traveling poet”—a phrase that captures his significance more precisely than any generic label.

Over more than six decades he created a body of work in which the continent’s political upheavals, its religious and cultural traditions, and the intimacy of an individual gaze upon streets, squares, and faces flow together.