The current discussion about artificial intelligence (AI) rarely stops at describing technical functionality. Instead, questions about its cultural, ethical and existential classification are increasingly coming to the fore.

ISLAMIC TIMES – Different schools of thought are pointing to possible ways of dealing with this technology – without immediately falling into progress euphoria or cultural pessimism.

AI – it’s high time Muslims got involved

It is high time that we Muslims, as an active part of civil society, formulate our position on how to deal with this technology. Byung Chun Han’s new book Talking about God reads like a kind of warning in this context. His thesis: ‘God is not dead. Dead is the man to whom God revealed himself.’

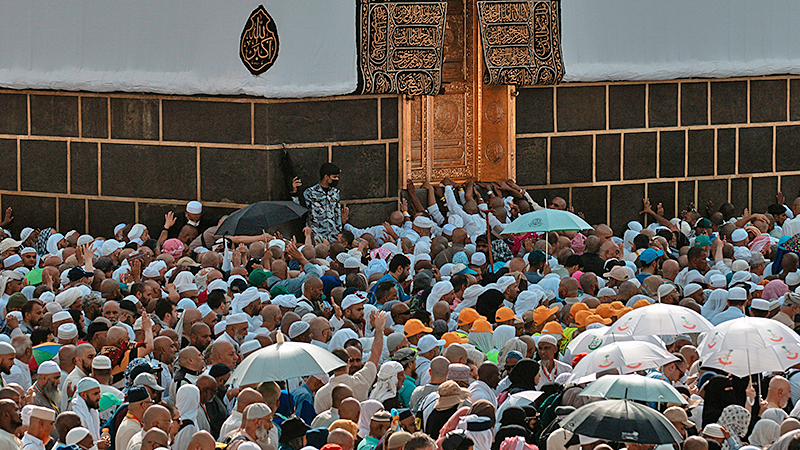

The symbiosis of social media and artificial intelligence collectively exposes us to the business model of the distraction industry. Even today, we read subtle reminders in our mosques asking worshippers to switch off their mobile phones during prayer.

Soon, it will be one of the noble tasks of our imams, who operate at the interface between the infosphere and the biosphere, to explain the basic prerequisites for a spiritual experience.

Without the ability to concentrate, pay attention and empty oneself, no spiritual experience can succeed, Han rightly claims. Appropriate training will be one of the key tasks of Muslim communities in the 21st century.

We need a sober view of technology

The necessary education includes offering a sober view of the fascination and pitfalls of modern technology. A frequently raised argument against the use of artificial intelligence is that it is ‘unsuitable’ because it ‘asserts incorrect facts,’ “hallucinates” or ‘invents abstract connections.’ Indeed, errors, incorrect attributions and implausible conclusions are documented phenomena in AI-generated texts.

However, these observations fall short when interpreted as proof of fundamental uselessness. AI language models are not truth machines. They are, by their very nature, models of linguistic probability.

Foto: Freepik.com

It was never about ‘truth’

Their functioning is not based on grasping truth in the philosophical or scientific sense, but on generating linguistically plausible answers – learned from countless patterns of human language. Let’s not forget: in our everyday language, we constantly assert incorrect facts – without any technology and often unconsciously – we skilfully conceal our gaps in knowledge and like to construct false ones.

We should see AI less as a miracle and more as a tool that can support us in our search for truth and meaning. Yes, the new language models will further ideologize ideologues, but they will also enable differentiation and balance.

In this context, we Muslims are committed to the paramount importance of intention, as emphasised by Imam Nawawi in his collection of hadiths. It is not a question of whether we use technology, but how and, above all, why. The demands are always the same: what brings us closer to the Creator, how do we organise our affairs in accordance with our intentions, and how do we move closer to a just society?

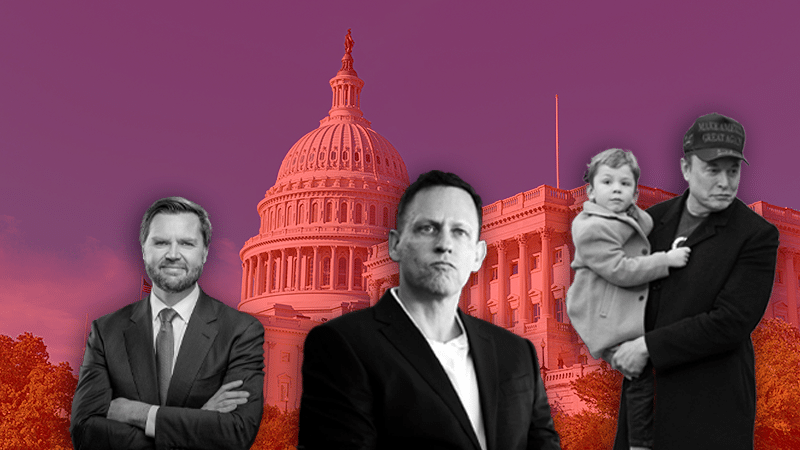

The statements made by leading figures in the digital industry contribute significantly to the scepticism surrounding artificial intelligence. In public statements, managers and founders of large technology companies often use rhetoric that conjures up the image of an all-encompassing, almost godlike intelligence.

From systems that ‘understand better than humans themselves’ to visions of a ‘superintelligence’ that can transcend human limitations, a narrative is being promoted that portrays AI as a power superior to humans. In the future visions of transhumanists and so-called post humanists, artificial intelligence takes on an almost metaphysical dimension.

Foto: Freepik.com

The next step in evolution or pseudo-religious ideology?

For thinkers like Ray Kurzweil (yes, we are creating a god!), superintelligence is not merely a technological development, but the next step in cosmic evolution. The mission of this superintelligence is to transform the entire universe into a thinking entity – matter itself is to become consciousness.

In this conception, technical progress culminates in a pseudo-religious goal: the creation of a universal mind, a machine deity. It is noteworthy that these visions have parallels in spiritual and religious models of thought.

The Jesuit and philosopher Pierre Teilhard de Chardin spoke as early as the mid-20th century of an ‘Omega Point’ – a destination point of evolution where biological, spiritual and technological developments converge. How do we respond to these fantasies?

Defending our narrative of creation and preserving our forms of wisdom is of paramount importance. Added to this is a link to the study of European philosophy, without which we cannot fully understand technology. In combination, we thus define an updated mission for Islamic education in the modern age.

‘Whether we like it or not, the idea that AI systems could surpass human judgement – or even humanity itself – has long been normalised in society.’ It is also ironic that we Europeans now fear the colonisation of our societies by so-called techno-feudalism (Varoufakis).

Art work: IZ Medien (all images are either CCL or public domain)

Scepticism towards human actors

Added to this is our scepticism towards the leadership myth of tech prophets: the idea that a select few – managers, engineers, investors – are working to establish a new, quasi-divine principle of order is somewhat disturbing. Technological fascination is accompanied by suspicion: is a power being established here that is beyond any democratic control?

As Muslims committed to the idea of justice, we are undoubtedly committed to defending civil society against the machinations of the global technology industry. We share the concern that technological progress threatens to turn into metaphysical hubris – and establish a new form of power that unfolds beyond ethical constraints.

The call for regulation and ethical limits should therefore also be understood as a reaction to this rhetoric of omnipotence: as an attempt to bring the tool of AI back within the realm of human standards. At the moment, important impulses are coming less from theology than from the world of philosophy, at the interface between wisdom and technology.

So-called New Stoicism, for example, propagates an attitude of serenity and self-discipline in the face of technological upheaval. The phenomenon of wisdom is fundamentally rooted in ancient Greek philosophy. AI is recognised not as a threat, but as part of a changing world.

However, the stoic attitude urges inner moderation: it is not technology that should determine the measure of human beings, but rather human beings who should preserve their intellectual autonomy vis-à-vis technology. The question of control – i.e. whether we control technology or it controls us – is of crucial importance here. This mindset is modern not least because it advocates universal human rights.

New realism, represented by philosophers such as Markus Gabriel, also argues for a sober view of reality. AI is understood neither as a panacea nor as an existential threat, but as a real, material technology that must be understood in terms of its range of effects and critically monitored. ‘AI cannot philosophise,’ the philosopher likes to remind his audience.

For him, the call for ‘technological openness’ goes hand in hand with a call for epistemic modesty and ethical reflection: God belongs to the worldview, humans remain the subjects of reality, AI is a tool. However, clever philosophers like Gabriel are not entirely sure whether the world of machines might not one day become independent.

Foto: Freepik.com

Do the major world religions have anything to say about this?

What could be the significance of the major world religions in this discourse? Their possible roles remain ambivalent: on the one hand, religious traditions can act as a spiritual counterweight by raising questions about meaning, dignity and responsibility beyond technological feasibility.

On the other hand, they too face the challenge of not closing themselves off to digital change but rather accompanying it critically and constructively. Religious arguments encounter reservations above all when they collude with profane power interests.

The Muslim community living in Europe is aware of the outstanding importance of a free civil society in this regard: how liveable would an ‘Islamic’ or ‘religious’ state be that uses AI, for example, to monitor the religious practices and virtues of its population? One would have to be blind not to see the abyss this would lead to.

What all ethically argued positions have in common is the insight that AI as a technology is neither good nor evil per se – but that its use can shape our worldview. Openness to technology alone is therefore not enough. Its development and use require an intellectual foundation that provides both an attitude and ethical concepts.

Last but not least, the question of regulation is also inevitable: as a means of limitation, but also as an expression of responsible freedom in dealing with technology.

Artificial intelligence has long since become a global cultural factor. Language models and AI systems generate content that is received by the masses and integrated into everyday communication processes. In doing so, they often influence the collective world view unnoticed.

They determine how connections are explained, how terms are defined and how problems are named. This effect goes beyond purely technical functionality: AI systems continue narratives, select information and shape patterns of interpretation.

This cultural influence raises an anthropological question: How is AI perceived by society? Does it remain a mere tool or is it beginning to be understood as a kind of ‘other’?

We are already seeing AI-supported systems being treated as seemingly autonomous conversation partners. Who hasn’t heard someone in their circle of friends say that they can have better, more balanced conversations with a machine than with most of their friends?

The consequences of AI platforms answering questions from Muslims and their answers gaining sway on social media are unclear. One thing is certain: the traditional role of mosques as places of lively, formative knowledge transfer is coming under increasing pressure.

If we Muslims can clarify how we intend to position ourselves with regard to technology in the future, we will be able to turn our attention to the numerous fascinating applications it offers. The idea of conceiving artificial intelligence not only as a technical tool but also as a vehicle for ethical judgement is becoming increasingly important, for example.

The aim here is not so much to equip machines with their own moral consciousness, but rather to programme systems that can incorporate and take ethical principles into account in their decision-making processes.

Such ‘ethically thinking AI agents’ could be used in various fields of application. In the halal economy, for example, agents could analyse and suggest suitable investment opportunities. In sensitive areas such as asylum procedures or social benefits, AI systems could help to ensure that automated decisions are not purely formalistic but take human dignity and social justice into account.

More generally, we might ask: Do we not share the hope of many experts that technological innovations yet unknown will solve the challenges of our time? Today, belief in a benevolent destiny unites believers of all stripes and opens up entirely new forms of dialogue.

In her new book, The New God, theologian Claudia Paganini shows the latest points of contact between metaphysics and the meta-project of artificial intelligence. In her comparison at the meta-level, she finds that the religious side lacks any reference to the practice of wisdom, the idea of heart formation and the importance of behaviour.

For her, it is not an exaggeration ‘to claim that in the secular, technologized age, humanity’s spiritual quest will increasingly take concrete form in the invention and worship of AI.’

Worshipping a machine would certainly not be the pinnacle of human history. Nor is it an option to question the phenomenon of technology in general.

This makes it all the more important to show that Islam is not abstract metaphysics, that it teaches more than just cold theology, that it does not strive for ideology, but rather embodies a way of life based on wisdom. This includes explaining our relationship to revealed language in relation to the systematics of modern language models.

One does not cry when artificially composed texts are recited. Only with heart and mind can one maintain one’s own balance in the age of technological revolutions.