Algorithms are changing our travel experience. The art of being in the right place at the right time.

ISLAMIC TIMES – Between departure boards, jet lag and endless scrolling on your smartphone, something strange sometimes happens: a journey begins as a plan – and ends as an experience that defies the plan. It’s as if time changes its form when we’re on the move.

Not because clocks tick differently, but because we are present differently. It is an art to be in the right place at the right time. To a certain extent, travelling can be experienced as a form of catharsis.

The art of travelling

The process of catharsis, i.e. emotional cleansing or purification, is not limited to art and theatre, but can also arise through intense, transformative experiences while travelling. Travelling, especially when it involves challenges and intense experiences, also leads to deep emotional cleansing.

Travelling not only allows us to escape everyday life and leave behind familiar, perhaps stressful or burdensome circumstances, but also creates a space for self-reflection and inner clarity.

Living in the right moment

One of the most impressive experiences of travelling is the existential experience of time. We are all familiar with the phenomenon: the time spent travelling can be long or pass very quickly. ‘Depending on our mood, our age or our activity, an hour can crawl by or race by, speed up or slow down, but on the clock, every hour is the same,’ writes philosopher Joke Hermsen.

In her fascinating book on the art of ‘Kairos’, she points to another experience of time that is also significant for us: ‘While Chronos stands for universal, static and quantitative time, which is necessary to place time in a linear context, Kairos stands for the subjective, dynamic and qualitative moment that takes into account specific and constantly changing circumstances and can therefore lead to a change in perception.’

When travelling, one should keep expectations high for these special moments, beyond the travel plans. We reflect on this dual nature of time: the difference between the chronologically imagined time and the moments when it holds the possibility of an expanded experience of consciousness.

We chronically have too little time – Chronos, the old man with the hourglass in his hand, symbolises the eternal passage of time, which we so often rush after.

For the Greek poets, Kairos was ‘everything that is good for man.’ In the moment of attention, we see a break in the usual chain of events and the possibility of real change.

At the beginning of the last century, the philosopher Henri Bergson wrote about the difficulty of finding oneself in modern times. ‘Most of the time, we live outside ourselves; we perceive only a colourless phantom of our ego, a shadow (…). We live more for the outside world than for ourselves (…) rather than acting ourselves, we are acted upon.’

Photo: Freepik

It’s hard to opt out

In these times, many travellers find it difficult to opt out of the flood of information that our smartphones constantly remind us of. Today, it is above all fear and depression, distraction and dissipation that endanger our inner lives.

‘Inner emigration no longer works because the infiltration of reality catches up with us in every place of retreat,’ philosopher Peter Sloterdijk aptly notes in an interview with the Augsburger Allgemeine newspaper. We must be careful – especially when travelling – with the external impressions that reach us. Distinguishing between what is actually important and what is not is one of the most significant exercises.

In Greek philosophy, it is tragedies that are supposed to show people how to cope with the emotions of fear and pity and lead to a ‘catharsis,’ a purification. According to Aristotle, ‘affects are emotions that cause people to change their mood and judge differently, emotions that are associated with feelings of pleasure and displeasure, such as anger, pity, fear and others of that kind, as well as their opposites.’

The philosopher argued that the influence of affects was not harmful. This is because the course of tragedies, with their resolution of conflict, frees us from the pressure of the emotions they arouse. His teacher Plato was sceptical about this form of purification. He generally feared that mental and emotional influences in the soul would develop a long-term, uncontrollable and often negative momentum of their own.

In this century, we are experiencing numerous tragedies, wars and challenges for which it is said that there are no longer any simple solutions. The flood of images, the depiction of violence and excesses, the multitude of true and false information unnoticeably influence our own state of mind. It is difficult to switch off. Today, especially when we think of irrational outbreaks of violence, we tend to take Plato’s objections more seriously again.

Gazing into the abyss does not remain without consequences

One thing is certain: gazing into the abyss of our time does not remain without consequences. Travel allows us to immerse ourselves in another dimension of ‘timeless’ experience.

Today, algorithms are changing the world of travel experiences.

However, the decisive moments on a journey cannot be planned. In reality, one often travels without knowing exactly what one is looking for and finds something unexpected: an encounter, a mood, a sentence that stays with one. Only in retrospect does it seem as if one was in the right place at the right time. Algorithms promise orientation. They calculate routes, suggest content and optimise time slots.

They know when to post, which route is the fastest, which decision would statistically be the best. Time becomes measurable, comparable, efficient. But what Kairos means eludes this logic. The right moment is not a point on the clock, but an event. It arises when attention, place and action coincide.

Photo: Abu Bakr Rieger

True travel makes this difference tangible

When you are on the road, you quickly realise that the plan is only a framework. Delays, detours and spontaneous decisions open spaces where something can happen. It is often the unplanned hours – staying instead of moving on, losing instead of finding – that give meaning. The place becomes important not because it was recommended, but because you were there.

This contrasts with the technical control of everyday life. Navigation systems know where you are, but not when something will happen. Recommendation algorithms deliver what is appropriate, but rarely what is decisive. They work with probability, not meaning. The ‘right moment’ is calculated, simulated, predicted – and in the process loses its openness. What happens is replaced by what is expected.

This also changes the concept of fate. In the past, it was considered uncontrollable, but today it appears as a subtle pre-structuring: which paths become visible, which people appear, which options seem realistic. It is not coercion, but rather guidance. Yet probability can feel like necessity. When everything is pre-selected, deviation becomes exhausting.

This is where Kairos comes in – not as a romantic counterpoint to technology, but as an attitude. It demands presence. Being in the moment does not mean holding on to everything but remaining attentive to what is revealed.

This can mean not interrupting a conversation, not leaving a place immediately, making a decision that is not optimal but coherent. Freedom then arises not through maximum choice, but through presence.

Kairos is not a retreat from modernity, but a reminder that meaning cannot be calculated. Algorithms can help us find our bearings. However, the decisive factor remains whether we are prepared to arrive. Perhaps this is a contemporary form of destiny:

Being in the right place at the right time does not mean being guided but remaining open – to the event that does not announce itself, but can change everything.

Photo: hafizismail, Adobe Stock

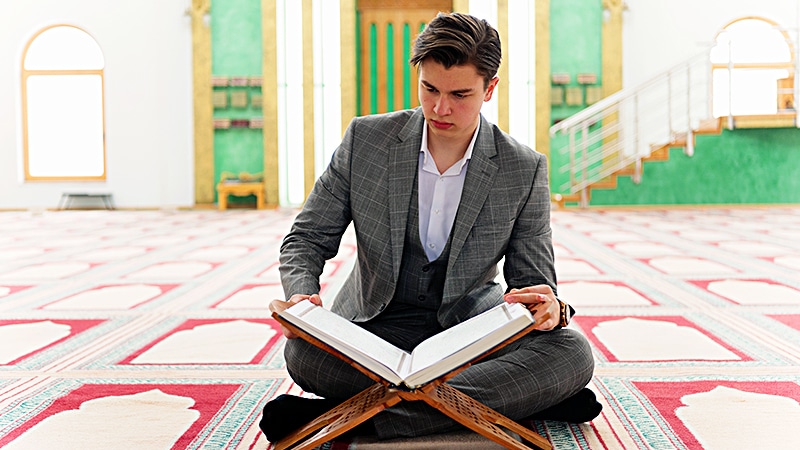

Islam also has concepts of time

This concept is not only Western philosophy. Islam also has the idea of a ‘specific time’ – a moment when something is fulfilled without it being possible to calculate it. One meets one’s destiny not because one has planned it, but because its time has come. People travel, make decisions, miss turns, stop or continue their way. But the event only occurs when the moment is ripe. Not earlier, not later.

Therein lies a striking similarity to kairos. Here, too, time is not a neutral continuum, but a carrier of meaning. The right moment cannot be forced, only recognised. It requires presence, not control. Action, yes – but without the illusion of being able to create the moment itself. Meaning does not arise from optimisation, but from fit.

It is precisely here that Kairos and the Islamic idea of predetermined time intersect as quiet counterpoints to technical control. They remind us that not everything that is decisive can be predicted. That the right place is not always where you are led.

And that the right time is not necessarily the most efficient. Perhaps this is a contemporary form of freedom: moving through a calculated world without being completely calculated. Following paths without knowing the moment – and only recognising it when you are there.

Photo: as-artmedia, Adobe Stock

Ajal: the appointed time

The Qur’an states several times that every life, every event, every community has a specific time: ‘Every community has a (fixed) term. And when their term comes, they can neither delay it for an hour nor advance it.’ (Sura 7:34)

The ‘appointed time’ is not a countdown, but rather a threshold at which something is fulfilled. God creates heaven and earth ‘in truth and for a specific time’ (cf. Sura 30:8). Time is conceived here in teleological terms: in terms of meaning, not measurement.

The parallel to Kairos is striking because both refer to qualitative time, placing meaning above measurability and often only recognised as ‘right’ in retrospect. In the Qur’an, the ‘appointed time’ is not a favourable moment in the pragmatic sense, but an existential one: when it occurs, something changes irrevocably.

In the end, perhaps that is the real lesson of travel: chronos takes us to places – kairos makes places resonate within us. You can book tickets, save routes, work through recommendations. But the moment that remains is rarely the optimised one.